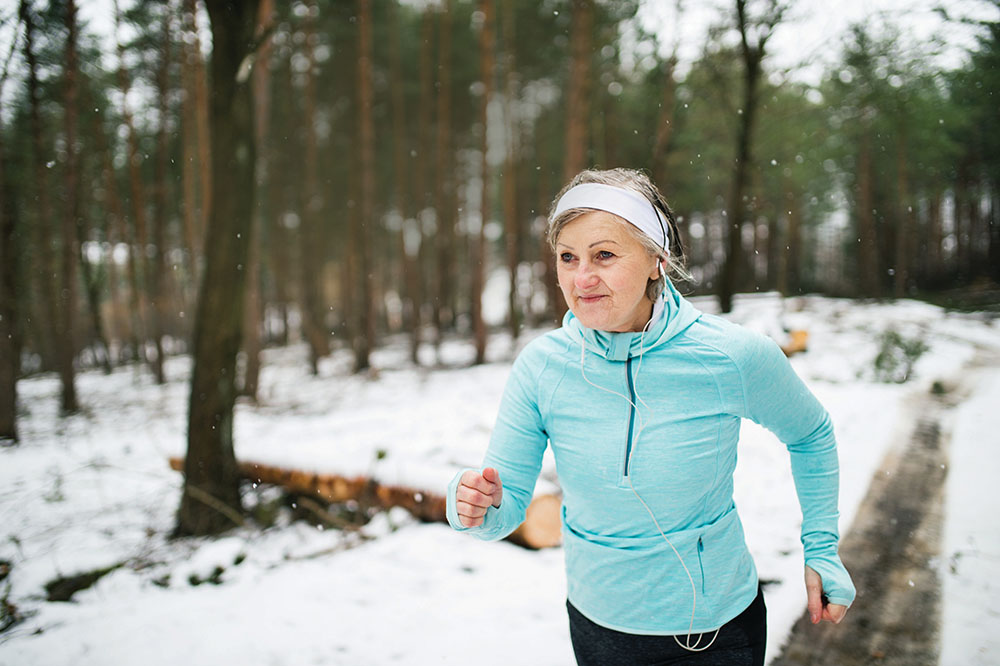

The benefits of regular physical activity occur throughout life and are essential for healthy aging. Adults age 65 years and older gain substantial health benefits from regular physical activity. However, it is never too late to start being physically active. Being physically active makes it easier to perform activities of daily living, including eating, bathing, toileting, dressing, getting into or out of a bed or chair, and moving around the house or neighborhood. Physically active older adults are less likely to experience falls, and if they do fall, they are less likely to be seriously injured. Physical activity can also preserve physical function and mobility, which may help maintain independence longer and delay the onset of major disability. Research shows that physical activity can improve physical function in adults of any age, adults with overweight or obesity, and even those who are frail. Promoting physical activity and reducing sedentary behavior for older adults is especially important because this population is the least physically active of any age group, and most older adults spend a significant proportion of their day being sedentary.

Older adults are a varied group. Most, but not all, have one or more chronic conditions, such as type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, osteoarthritis, or cancer, and these conditions vary in type and severity. Nevertheless, being physically active has significant benefits for all older adults. Physical activity is key to preventing and managing chronic disease. Other benefits include a lower risk of dementia, better perceived quality of life, and reduced symptoms of anxiety and depression. Additionally, doing physical activity with others can provide opportunities for social engagement and interaction. All older adults experience a loss of physical fitness and function with age, but some experience this more than others. This diversity means that some older adults can run several miles, while others struggle to walk a few blocks.

Key Guidelines for Older Adults

Adults should move more and sit less throughout the day. Some physical activity is better than none. Adults who sit less and do any amount of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity gain some health benefits.

Aerobic Activity

Aerobic activities, also called endurance or cardio activities, are physical activities in which people move their large muscles in a rhythmic manner for a sustained period of time. Brisk walking, jogging, biking, dancing, and swimming are all examples of aerobic activities. Aerobic activity makes a person’s heart beat more rapidly and breathing rate increase to meet the demands of the body’s movement. Over time, regular aerobic activity makes the cardiorespiratory system stronger and more fit. No matter what the purpose—from walking the dog, to taking a dance or exercise class, to bicycling to the store—all types of aerobic activity count toward meeting the key guidelines. When putting the key guidelines into action, it is important to consider the total amount of activity, how often, and at what intensity. For health benefits, the total amount of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity is more important than the length of each physical activity episode. In general, muscle-strengthening activities do not count toward meeting the aerobic key guidelines.

How Much Total Activity a Week?

Older adults should aim to do at least 150 to 300 minutes of moderate-intensity physical activity a week, or an equivalent amount (75 to 150 minutes) of vigorous-intensity activity. They can also do an equivalent amount of activity by doing both moderate- and vigorous-intensity activity. As is true for people of all other ages, greater amounts of physical activity provide additional and more extensive health benefits. Older adults who do more aerobic physical activity have a reduced risk of age-related loss of function and reduced risk of physical function limitations compared to the general aging population. Older adults should strongly consider walking as one good way to get aerobic activity. Walking has many health benefits, and it has a low risk of injury. It can be done year-round and in many settings.

How Many Days a Week and for How Long?

Aerobic physical activity preferably should be spread throughout the week. Research studies consistently show that activity performed on at least 3 days a week produces health benefits. Spreading physical activity across at least 3 days a week may help to reduce the risk of injury and prevent excessive fatigue. All amounts of aerobic activity count toward meeting the key guidelines if they are performed at moderate or vigorous intensity. Episodes of physical activity can be divided throughout the day or week, depending on personal preference.

How Intense?

The intensity of aerobic activity can be tracked in two ways—absolute intensity and relative intensity. Most studies on older adults use relative intensity to track aerobic physical activity. When using relative intensity, people pay attention to how physical activity affects their heart rate and breathing. As a rule of thumb, a person doing moderate-intensity aerobic activity can talk, but not sing, during the activity. A person doing vigorous-intensity activity cannot say more than a few words without pausing for a breath.

Muscle-Strengthening Activities

At least 2 days a week, older adults should do muscle-strengthening activities that involve all the major muscle groups. These are the muscles of the legs, hips, chest, back, abdomen, shoulders, and arms. The improvements in, or maintenance of, muscular strength are specific to the muscles used during the activity, so a variety of activities is necessary to achieve balanced muscle strength.

Muscle-strengthening activities make muscles do more work than they are accustomed to during activities of daily life. Examples of muscle-strengthening activities include lifting weights, working with resistance bands, doing calisthenics that use body weight for resistance (such as push-ups, pull-ups, and planks), climbing stairs, shoveling snow, and carrying heavy loads (such as groceries and heavy gardening).

Muscle-strengthening activities count if they involve a moderate or greater level of intensity or effort and work the major muscle groups of the body. Whatever the reason for doing it, any muscle-strengthening activity counts toward meeting the key guidelines. For example, muscle-strengthening activity done as part of a therapy or rehabilitation program can count.

No specific amount of time is recommended for muscle strengthening, but muscle-strengthening exercises should be performed to the point at which it would be difficult to do another repetition. When resistance training is used to enhance muscle strength, one set of 8 to 12 repetitions of each exercise is effective, although 2 or 3 sets may be more effective. Development of muscle strength and endurance is progressive over time. That means that gradual increases in the amount of weight, number of sets or repetitions, or the number of days a week of exercise will result in stronger muscles.

Balance Activities

These kinds of activities can improve the ability to resist forces within or outside of the body that cause falls. Fall prevention programs that include balance training and other exercises to improve activities of daily living can also significantly reduce the risk of injury, such as bone fractures, if a fall does occur. Studies of fall prevention programs generally include about three sessions a week. Balance training examples include walking heel-to-toe, practicing standing from a sitting position, and using a wobbleboard. Strengthening muscles of the back, abdomen, and legs also improves balance.

Flexibility, Warm-Up, and Cool-Down

Older adults should maintain the flexibility necessary for regular physical activity and activities of daily life. Flexibility activities enhance the ability of a joint to move through the full range of motion. Stretching exercises are effective in increasing flexibility, and thereby can allow people to more easily do activities that require greater flexibility. Although the health benefits of these activities alone are not known and they have not been demonstrated to reduce risk of activity-related injuries, they are an appropriate component of a physical activity program. However, time spent doing flexibility activities by themselves does not count toward meeting the aerobic or muscle-strengthening key guidelines.

Research studies of effective exercise programs typically include warm-up and cool-down activities. A warm-up before moderate- or vigorous-intensity aerobic activity allows a gradual increase in heart rate and breathing at the start of the episode of activity. A cool-down after activity allows a gradual heart rate decrease at the end of the session. Time spent doing warm-up and cool-down activities may count toward meeting the aerobic activity guidelines if the activity is at least moderate intensity (for example, walking briskly to warm up for a jog). A warm-up for muscle-strengthening activity commonly involves doing exercises with less weight.

Meeting the Key Guidelines

Older adults have many options for how to live an active lifestyle that meets the key guidelines. Many factors influence decisions to be active, such as personal goals, current physical activity habits, and health and safety considerations. In all cases, older adults should try to move more and sit less each day. In working toward meeting the key guidelines, older adults are encouraged to do a variety of activities. This approach can make activity more enjoyable and may reduce the risk of overuse injury.

Healthy older adults who plan gradual increases in their weekly amounts of physical activity generally do not need to consult a health care professional before becoming physically active. However, health care professionals and physical activity specialists can help people attain and maintain regular physical activity by providing advice on appropriate types of activities and ways to progress at a safe and steady pace.

Older adults with chronic conditions should talk with their health care professional to determine whether their conditions limit, in any way, their ability to do regular physical activity. Such a conversation should also help people learn about appropriate types and amounts of physical activity.

Inactive and Insufficiently Active Older Adults

Some physical activity is better than none. Older adults who do not yet do the equivalent of 150 minutes of moderate-intensity physical activity a week can gain health benefits by doing small amounts of physical activity. In addition, swapping out sedentary behavior, such as sitting, for light-intensity physical activity, such as light housework, may produce some benefits. There are even more benefits to sitting less and doing moderate- or vigorous-intensity physical activity. The biggest gain in benefits occurs when going from no physical activity to being active for just 60 minutes a week.

Older adults should increase their amount of physical activity gradually. It can take months for those with low fitness to gradually meet their activity goals. To reduce risk of injury, it is important to increase the amount of physical activity gradually over a period of weeks to months. For example, an inactive person could start with a walking program consisting of 5 minutes of slow walking several times each day, 5 to 6 days a week. The length of time could then gradually be increased to 10 minutes per session, 3 times a day, and the walking speed could be increased slowly.

Muscle-strengthening activities should also be gradually increased over time. Initially, these activities can be done just one day a week starting at a light or moderate intensity. Over time, the number of days a week can be increased to two, and then possibly to more than two. Each week, the intensity can be increased slightly until it becomes moderate or greater.

Information from: Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans, 2nd edition | 2018 U.S. Department of Health and Human Services